Discover more from The Accessibility Apprentice

The immense potential of AR/VR for accessibility

Discussing current and prospective applications and limitations of AR and VR for accessibility

In 1950, Ray Bradbury (who, hopefully, doesn’t need an introduction) published a short story, titled “The Veldt”, depicting a future household, filled to the brim with gadgets, devices, and machines. Bradbury’s portrayal of an automated house was not novel in and of itself, but he didn’t stop at imagining robots that do dishes and iron clothes.

The children in “The Veldt” spent most of their time in a nursery, a virtual reality room, capable of realistically depicting any environment they could possibly think of. Bradbury turned a utopian techno-dream into a nearly prophetic critique: if machines could replace us at work, could they also do so at home? What would he say of the children, glued to their iPads today?

Today, Bradbury’s fantasy doesn’t sound unrealistic: AR and VR may not be as advanced yet, but they show a tremendous potential, and their prospective applications are plenty, from entertainment and education to healthcare and wellness. More than that, AR/VR gadgets may help shape a more inclusive digital future by democratising access to technology: they come in many shapes and forms, use the body as the main input device, and adjust to their user’s unique needs and preferences.

In this issue of “The Accessibility Apprentice”, we will discuss how AR and VR devices may be the future of the inclusive world, and what it will take to realise their true potential for accessibility.

This newsletter remains free thanks to the power of will and passion for accessibility. You can support the author by buying him a cup of coffee.

Inclusive, Augmented, Real

Although technically, AR and VR are different technologies, it won’t be a stretch to bundle them together conceptually, as tools for deep, multidimensional immersion in the digital world. Augmented Reality brings virtual elements into the real world, while Virtual Reality creates entirely new environments, but devices like Apple Vision Pro demonstrate how both concepts can live within a single gadget.

AR and VR add a third dimension to the virtual experience, relying heavily (as compared to traditional digital devices) on natural means of sending commands and navigating the environments: from moving your phone around the room to using hand gestures and moving your entire body. In many ways, this already makes the experience more inclusive by erasing the learning curve: with every interaction being as intuitive as its real world counterpart, it should take no time to master them in the virtual reality. On top of that, much like in the real world, the user can choose how they wish to engage with the virtual realm, having the option to click virtual buttons or use a real-world input device, like a keyboard.

The increased levels of immersion and a flat learning curve give mixed reality experiences a strong advantage in certain fields, such as education and entertainment, and present them as near perfect solutions for accessibility, at least in theory.

Be (more than) my eyes

When mentioning AR for accessibility, augmented reality assistance for people with vision impairment often comes to mind first.

Be My Eyes is a mobile app that helps people navigate the real world by connecting its blind and low-vision users with volunteers to assist them through live video. The company behind the app specialises in developing solutions for accessibility—from mobile apps for individual users to accessible AI customer support for companies—some of which are fully automated, unlike the consumer app.

Automation is part of the appeal of AR/VR for accessibility, unlike traditional tech and the real world, which largely rely on other humans for assistance. Check out our previous issue, covering, among other things, the challenges, faced by the low-vision travellers.

In practice, however, AR and VR tech are yet to find their opportunities for wider adoption (especially VR, with its current somewhat unaffordable price tag). Low-vision users were the first (and arguably, the most obvious) candidates for adopting AR (researchers even coined the term AR4VI — Augmented Reality for Visual Impairment), and back in 2017, there were already multiple live apps and countless prototypes for object recognition and real-world navigation.

As the research continues, more areas begin to demonstrate potential. The future is slowly taking shape in the research labs, where the concepts are being developed, striving to blur the threshold between the worlds and remove the barriers for people with disabilities. These concepts draw from the same inspiration: to make more real world interactions accessible using augmented and virtual reality.

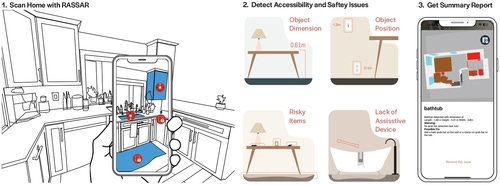

In 2023, a group of researchers presented RASSAR: a concept of an augmented reality app that scans indoor environments for potential hazards. It uses the phone’s camera to identify the dangers—from cluttered walkways to flammable objects in proximity to fire—and compiles a short actionable report.

Another group presented a VR prototype that helped low-vision users recognise tennis balls in real time. Although the researchers quote the “size, bulkiness, and limited field of vision” as the obvious limitations of the prototype, the discovery concludes: with some necessary adjustments and improvements to the core technology, VR has a great potential for making high-intensity sports more inclusive for players with low vision.

All things considered, there come two questions.

First: what would it take to turn the research prototypes into working products? Second: what else are AR/VR as tools for accessibility capable of, beyond complementing (or replacing) their user’s vision? The former may not have an easy answer: there are too many factors at play, including the limitations in technology. The latter has a lengthy, but a rather fascinating response.

Virtual entertainment and education

Education and entertainment are other obvious candidates for being the early adopters of AR/VR.

Sky Map is a mobile app for stargazers that highlights constellations, planets, and other space objects as the user’s camera is pointed at them. Originally developed at Google and later open sourced, Sky Map inspired a plethora of similar applications (for instance, an immensely popular Sky Guide with over 330K ratings on AppStore) for entertaining education across realities.

But AR and VR have long ventured further into the realm of science fiction with platforms like JigSpace that enable the creation of detailed 3D models for product demos and classrooms. Part of JigSpace’s unique selling proposition is accessibility and affordability: “presentations are automatically viewable, without an app, on any iOS, Android or desktop device”, which removes (or at the very least, significantly reduces) the ever so present adoption barrier.

AR/VR’s potential for education, communication, and entertainment is nearly unlimited, and the world is finally beginning to view it as more than a gimmick. We’ve talked about how modern museums employ technology to create immersive, accessible experiences on “The Accessibility Apprentice”.

There is no doubt, augmented and virtual realities make education more fun. The big question here is, do they also make it more accessible?

AR/VR for everyone

In 2022, an accessibility consultancy Equal Entry, in partnership with the research group adXR, published a study, examining how people with visual impairments could navigate virtual immersive environments. The study attempts to demonstrate that although VR technology cannot be used by the blind people, it may be made accessible to them with some improvements and considerations for the needs of users with disabilities.

Imagine a virtual library, a shop, or a conference hall, where users can explore the environment, interact with the objects and each other, and make purchases. What would it take to make this experience accessible to blind users, and how different would it really be from any other digital experience?

In some ways, using voice commands and gestures should make it easier for the blind users to interact with the environment, but the system will need to provide timely and accurate feedback. Equal Entry’s study highlights the critical importance of audio descriptions in VR for the users with visual impairment: from comprehending the context to understanding the results of their actions. For instance, one of the users tried grabbing a digital object, but “did not know if the item was in his hands because he did not receive any audio notification”.

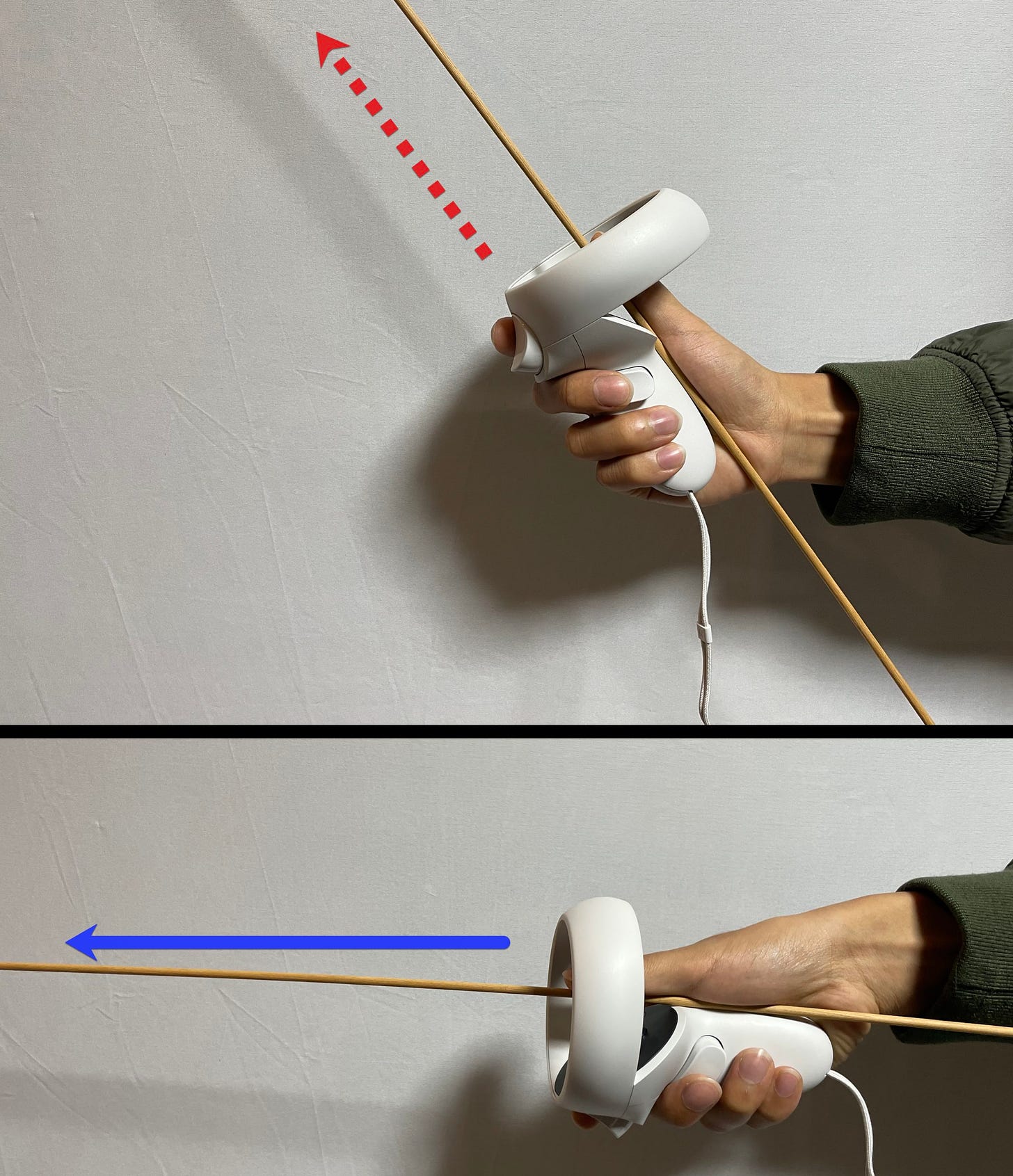

On top of that, the hardware’s lack of consideration for the blind users leaves them confused and incapable of performing interactions in the virtual environment: for instance, pointing the raycast forward proved to pose a challenge, possibly because “some participants are accustomed to using a white cane that points down while the raycast points forward”.

With the opportunities that AR/VR present for all areas of life, from shopping to education, making virtual experiences inclusive is more than desirable. Its novelty and immaturity are a big advantage: accessibility considerations can be embedded into the technologies and the products from the very beginning. Inclusive virtual spaces will create new markets, spanning from entertainment to rehabilitation and mental wellness, and significantly expand the user base, bringing the digital experiences closer to people with disabilities.

AR/VR devices are slowly becoming more advanced: long gone are the early days of the bulky, expensive sets that would make an astronaut nauseous, today’s gadgets look sleek, function surprisingly well, and the price tag is slowly but gradually getting lower.

I sincerely hope that spatial computing, virtual reality, and natural commands will remove the barriers, making the digital world inclusive and welcoming. It will take time, determination, and hard work to ensure that these new devices acknowledge and fix the limitations, created by their mobile and desktop predecessors, but I’d like to believe that the future we are marching towards is bright and accessible.