Discover more from The Accessibility Apprentice

Accessible museums: beyond labels

How exhibitions bridge the gap between physical, digital, and transcendental, and stay accessible.

I love museums as much as any other nerd. Museums are meant to be inclusive, all-welcoming spaces, and as such, must be designed carefully, with plenty of attention to detail: from wheelchair ramps and wide corridors to colour coding and labels in Braille.

Today, we will look at two of the most fascinating examples found in the wilderness. First, an exhibition centre that uses multisensory stimulation. Second, a museum that turns a regular visit into an unforgettable (accessible) digital ride.

This issue consists of ~960 words and will take about 5 minutes to read.

This newsletter remains free thanks to the power of will and passion for accessibility. You can support the author by buying him a cup of coffee.

Do you smell it?

There is a museum in the York (England) called Jorvik Viking Centre.

Built on top of the former archaeological site, the museum is famous for how it uses the “smells of Viking-age York” to capture the atmosphere of the past. It literally teleports its visitors into the 10th century with its scented halls, holograms, and entertainment.

Jorvik Centre is a good example of how non-verbal signalling and sensory activation is used for entertainment and learning. Smells and sounds make the experience not only more joyful, but also more accessible by driving immersion beyond visual stimulation.

Complete with the rollercoaster rides, workshops, and performances, the centre demonstrates the alternative to a traditional visual-only stimulation.

Who needs labels anyway?

There once was a boy named David

And then, there is MONA, the “Museum of Old and New Art” in Tasmania, where I happen to reside. MONA was founded by David, a professional gambler and art collector, who was hell-bent on making museums cool again.

MONA is a bizarre place (in the best possible sense): located underground, it features an ever-changing collection of modern and classical art, from mummies to the infamous poo machine.

MONA doesn’t like labels, and their walls, floors, and ceilings only feature art works with no distractions. Instead, the museum encourages visitors to download and use a special app that detects art works nearby and presents them to the user, together with any and all additional content.

This raises some accessible eyebrows at first. But only at first.

The MONA experience

A visit to MONA begins with a trip on a cruise ship to a remote location, a 99 steps climb (with an accessible tunnel available!), and an app.

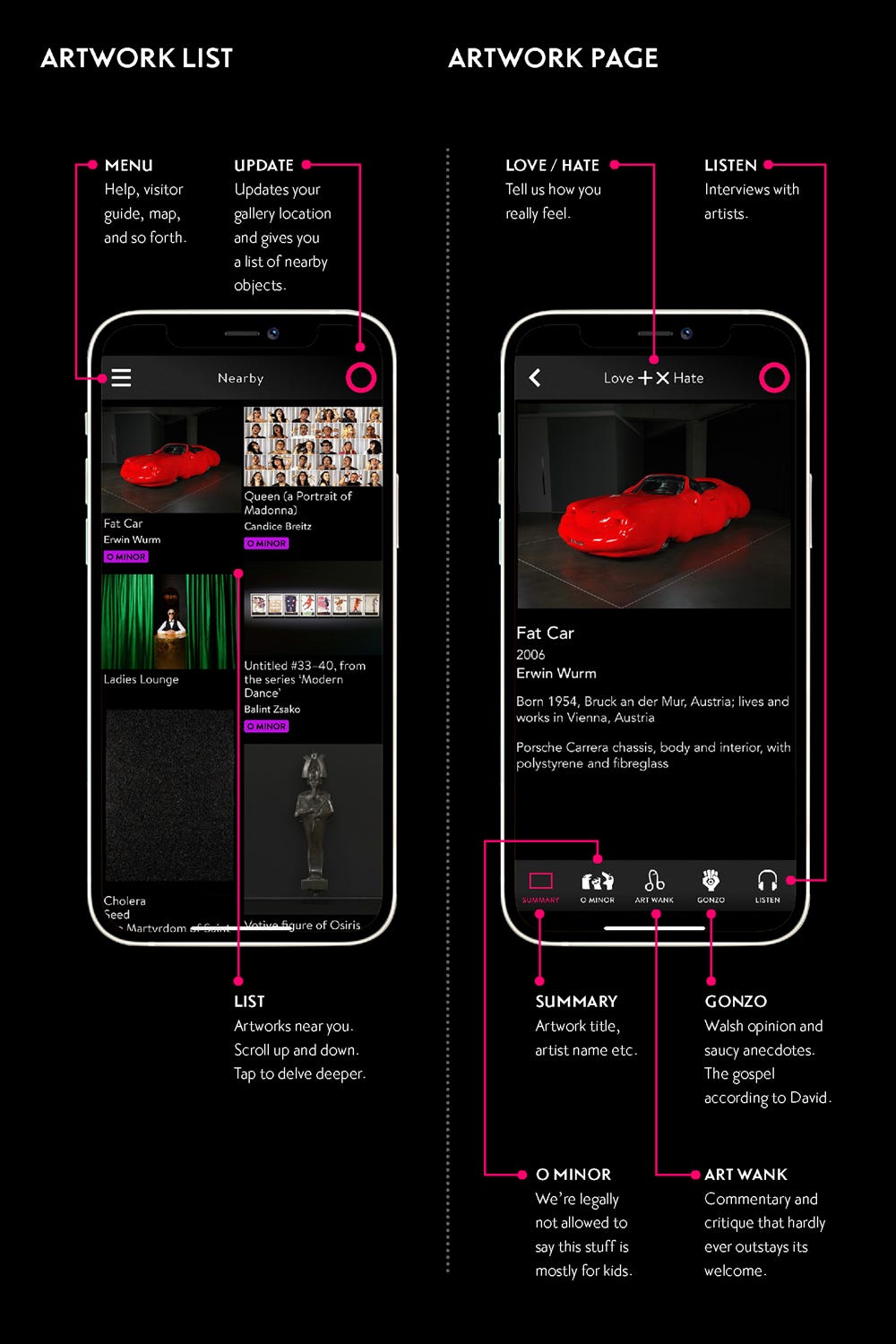

“The O” is the museum’s official mobile app that replaces labels, commentary, and any other materials one might need to discover and appreciate art. MONA has a free WI-FI, so bandwidth is not an issue, and plenty of QR codes and links to follow, so discovering the app is not a problem either.

As a tech connoisseur, I applaud the attempt to fully digitise the experience. The O uses Bluetooth to identify artworks nearby, and lists them out in a masonry grid.

It goes beyond replacing labels: it provides commentary, features David’s reviews, interviews with the authors and critics, and even has a “Love-Hate” button, allowing visitors to leave comments and share their (often bad) takes.

A visit to MONA made me believe this could be the second-best possible way for a museum to provide a truly inclusive experience, and that cultural centres, exhibitions, and events have a lot to learn from how David’s team handled crafting The O.

MONA and Accessibility

“The O” (and MONA in general) handles every experience within the museum walls gracefully: from its online tickets that glow in gradient until they are redeemed to managing queues at the attractions.

“The O” is more than a catalogue of art: it is a museum inside a museum, an experience in and of itself. Art Processors, the agency behind The O, explains: “Walsh […] wanted visitors to enjoy the artworks in an aesthetically pleasing space, and deliver rich content in an individual manner without distracting from the aforementioned aesthetic.”

What pleases me, however, is not the aesthetics, although I can’t help but praise The O’s pleasantly minimal design. My true excitement kicks in when I turn the Voiceover on, launch the app, and hear the beautiful robotic voice announce:

“We have made sure that the name of every art work is correctly exposed to Voiceover”

Here, I collapse, thrilled beyond belief, and bow to express my deepest gratitude to the caring people behind The O.

Here’s to the future

Museums are (meant to be) inclusive. They cater to every visitor, standing firmly between education and entertainment, and have the responsibility of making everyone comfortable and immersed.

We no longer come to museums to walk past glass coffins, glancing at the boringly arranged artefacts. The exhibition floor is the place of self-expression for the artist, where visitors are invited to watch, listen, play, and rest.

Modern museums never cease to impress. Jorvik Viking Centre sets a fascinating example of an olfactory-augmented experience in the wilderness. MONA delivers a perfectly accessible “phygital” space.

We may debate the convenience of using a mobile phone as a replacement for old-school labels. Someone could make a good case against scented exhibitions. Undoubtedly, some people would die defending a dim-lit hall with tiny labels underneath highlighted artworks as the golden standard.

It would be hard, however, to argue that by challenging the standards and bending the rules, these spaces made themselves more inclusive, and that, in my book, makes it all worth the effort.