Discover more from The Accessibility Apprentice

ADHD vs PhD: how I was (not) writing my research plan

A very personal story about how I'm trying to hit the most important milestone in my PhD journey so far, and how ADHD turns learning into a less than joyful adventure

This week, I am submitting my research plan: a huge document, outlining the scope of my thesis work and convincing the readers that the objectives are worth pursuing. My supervisors are supportive, understandable, and caring, and I've made some good progress over the past 3 months, having developed what looks like a comprehensive proposal.

And yet, I am not popping the champagne or putting on my celebratory pyjamas. In fact, I am quite exhausted from the sprint, too weary to even feel the satisfaction of hitting the first critical milestone on my path towards becoming a Doctor of Philosophy.

In this rather unusual issue of “The Accessibility Apprentice” I will share how my ADHD almost ruined what was supposed to be a joyful experience of discovery and research, how modern education pretends to consider the needs of individuals with mental impairments, and how to find a silver lining in every dark neurodivergent cloud.

This newsletter remains free thanks to the power of will and passion for accessibility. You can support the author by buying him a cup of coffee.

Look, mum, I’m a scientist

Just like every good workout starts with a few minutes of stretching, a PhD begins with a research plan: a wordy document that outlines the background of your future work, frames The Research Question™, and explains the methodology. I briefly mentioned it in my previous post about Universal Design and Paperwork.

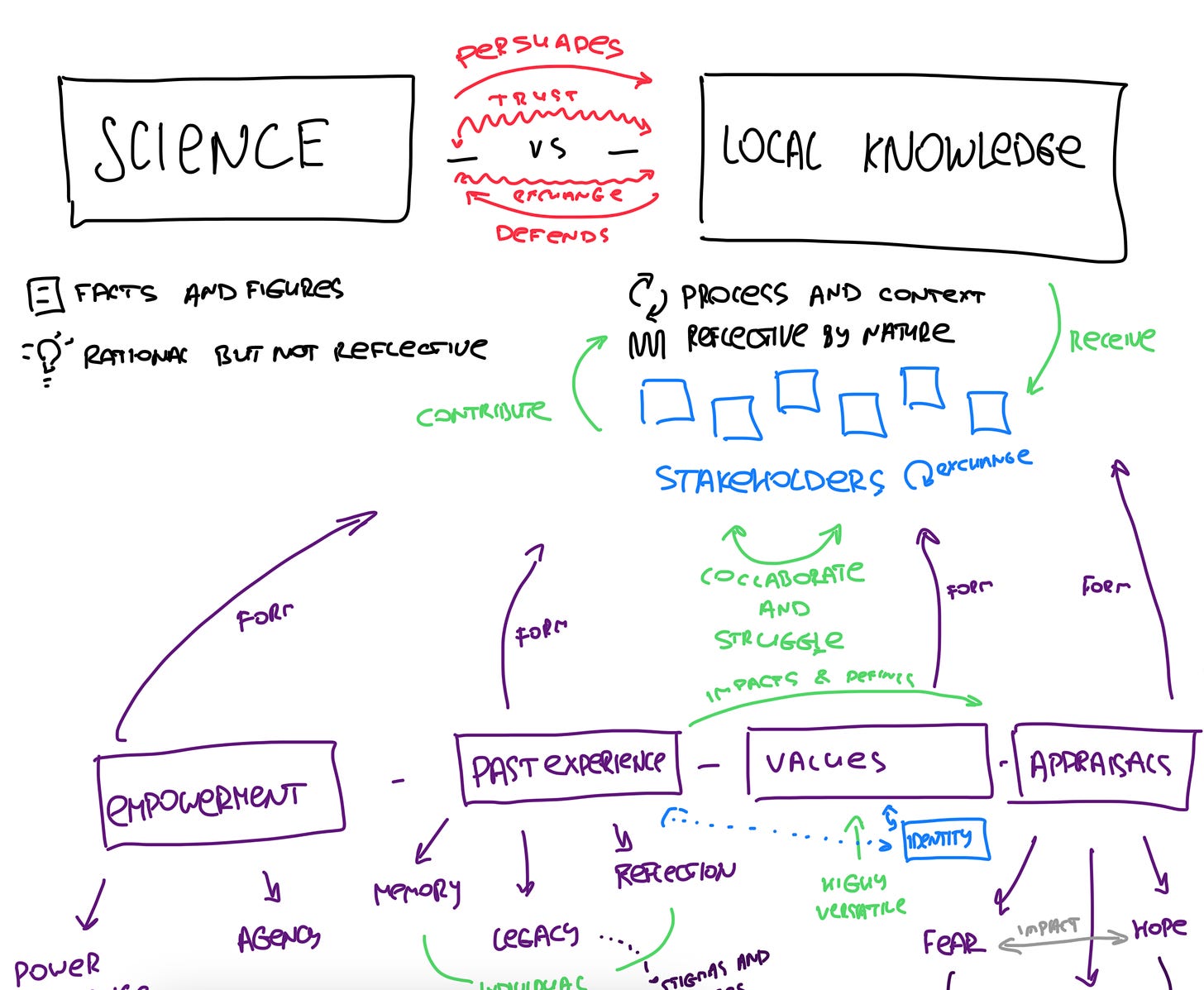

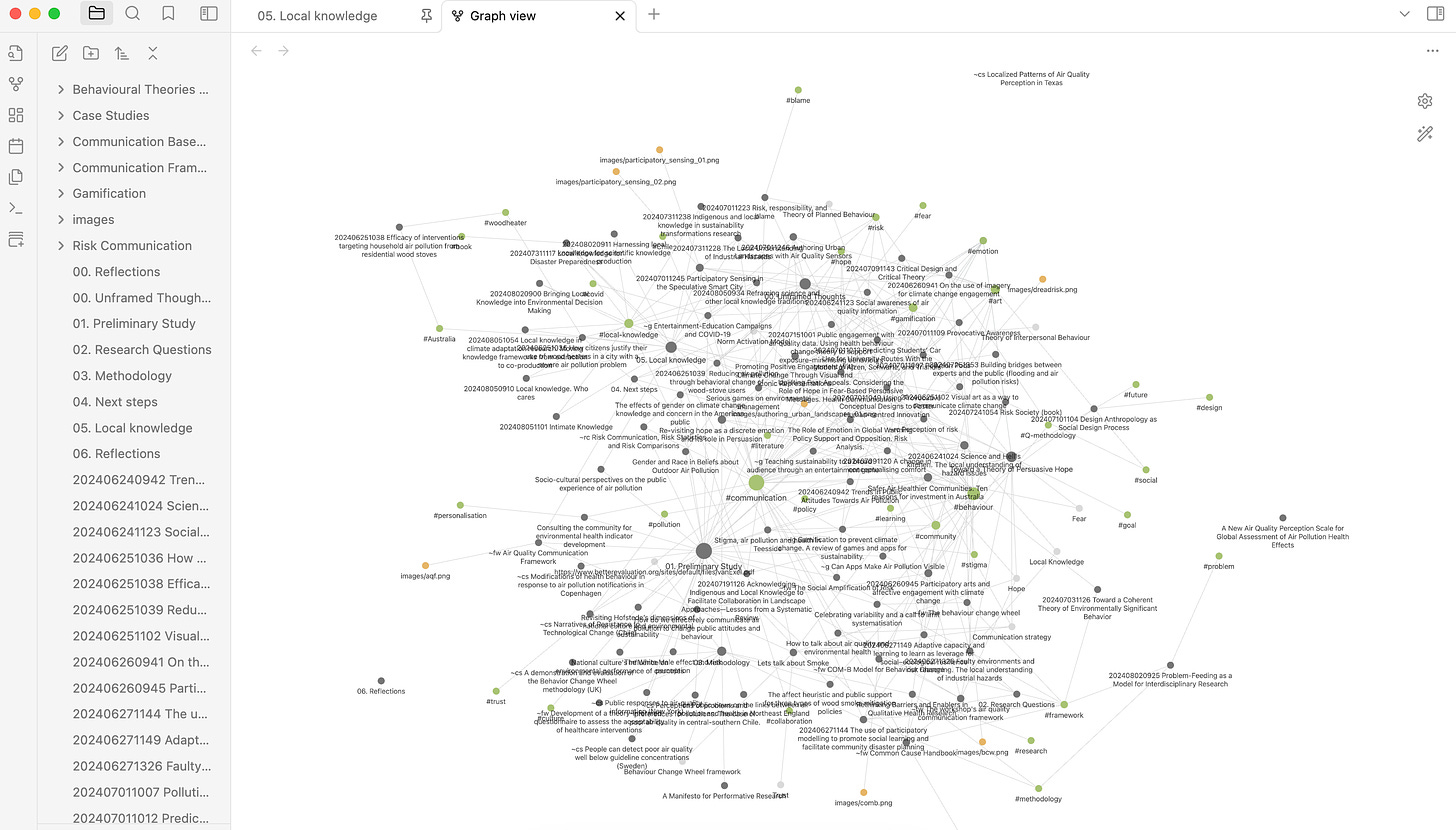

On 20 May 2024, I officially became a PhD Candidate at the University of Tasmania. I was handled a laptop, a monitor, and a task to surrender the first draft of a research plan within 3 months. I unpacked the laptop, installed the monitor in my new cubicle, and set up an Obsidian vault, hopeful that this time, I would finally be able to keep my learning neatly organised with a sophisticated system of tags, labels, and collective notes.

Oh, sweet summer child.

Science says

Problem: people with ADHD struggle to fit in the academia.

There are many studies that examine the learning styles of people with ADHD (mostly, children or young adults), and I, reflecting on the long and painful process of composing a plan for my future study, notice some being extremely pronounced in me.

For instance, this PhD Thesis titled “Significant Learning Experiences of Adult Learners with ADHD” recommends, among other things, that facilitators “provide flexibility in class assignments” and remember that learners with ADHD “may need clearer guidelines”.

This research concludes with an interesting discovery that children with ADHD may be more productive in the afternoon in soft light, and do not like reading or listening to lectures, instead opting for information presented through “kinaesthetic and tactile instructional resources”.

But the findings from this study really hit close to home: it assessed the coping strategies that people with ADHD employ, and found that the participants

lacked planful problem-solving, i.e. they lacked an ability to outline a plan of action and follow it. Thus they may be unable to think and plan ahead and, in response, become confrontational.

So on top of being allergic to reading, writing, learning, and working, I possess an impaired ability to plan. How am I supposed to write a detailed plan then?

Solution: one of my supervisors proposed that I see this as an opportunity to

design my dream project

Start by following your heart, and leverage your ability to think creatively, granted to you by your cruel mental impairment, as a consolation prize. Imagine a version of yourself that followed his heart and became an archaeologist, digging up a mummy, or a writer, locked in a cabin in the woods working on his new novel.

How would they approach your project? What would they do to answer your Research Question™?

So, in 3 days or less, my research plan was ready. In my head.

Studies as a form of torture

As a PhD student, you are expected to demonstrate the ability to work independently. There are some milestones for you to hit: team meetings, research plan, candidacy confirmation, but in general, you work at your own pace. Good luck.

I enjoy being in charge of my life, but at times, I feel overwhelmed. The world of academia, as I get to learn, doesn’t seem to be quite as reflective as it pretends to be.

For instance, practice-led research, a method of answering the research question through practice (often, creative practice), took a long time to establish its credibility and convince the scientific community that a researcher can produce knowledge through the means of making. Practice-led research embraces ambiguity and doesn’t often conform to the rigid structure of a “traditional” research practice.

And yet, you are expected to produce a plan that, among other things, includes budget estimates and key milestones. Don’t know yet where the adventurous road of discovery might lead you? Good joke, now go and write a 3-year plan.

Don’t get me wrong, I understand the value of planning and appreciate having some structure. I am no stranger to writing detailed project plans. The importance of a timeline for a long and complex research project is obvious. In fact, this “plan” is not a plan at all, but a “draft”, a first rough cut of what will eventually become a foundation for the thesis.

And yet, at times, I can’t help but feel lost, because the mere presence of a rigid plan makes me nervous. Instead of seeing it as a flexible set of checkpoints, I perceive it as a timetable, a list of deadlines I have to work against. “Clearer guidelines” turn into commandments: I either follow them to the T or suffer the consequences, no matter how many times I repeat the mantra: “you can always change it later”.

Discipline not punish

In his 1975 book, Discipline and Punish, a French philosopher Michel Foucault argues that the emergence of the modern institutions forged the need for discipline as a form of control and a mean of creating functioning bodies for the industrial age. Foucault brings up prisons, hospitals, and schools as examples of institutions that exercise precise control over bodies.

The birth of a more reflective, critical, and inclusive approach to education, labour, and science in the post-industrial age have seemingly transformed the institutions once more. Gone are the days of learning books by heart, and corporal punishment is no longer acceptable in most (but not all) countries of the civilised world.

Accessibility plays an important part in today’s education (and, to a certain extent, the labour market, too). “Necessary adjustments”, from ergonomic chairs and screen readers to wheelchair accessible classrooms and extended deadlines, are introduced for the mutual benefit of the learner, who is given a chance to study comfortably, and the society that invests in nurturing another productive contributing member.

We have certainly come a long way from ostracising people with disabilities to emphasising the importance of inclusive physical and digital spaces in learning, from demanding 7-year-old first-graders to sit still in class to advocating for gamified learning.

I sincerely hope that in the end, inclusive learning will nurture a society with an inclusive mindset, which in turn will make my job as an accessibility advocate obsolete. In the meantime, I am immensely grateful for the support I receive, privileged to be accepted and acknowledged as a member of the scientific community, and a tad anxious, thanks to another assignment with a rubric attached.

I have very much enjoyed reading ADHD vs PhD. Some aspects remind me of some of the ups and downs during my own doctoral studies and later on. I recognise too well - although I don't think I that big cloud of multiply interconnected dots, but sometimes, all you need is to give it time, decanting time. And all becomes clear. The key then, is not to turn completely mad till it happens!

Good luck for your PhD!